Caynham Village, Shropshire

Caynham Village History

Early History -

Caynham – an Anglo-

Let’s go back 400 million years when life on earth had only been going on for 150–200

million years and was still only in the sea. We were much nearer the equator then

and ‘Caynham’ was in the middle of a shallow warm coral sea. The evidence for this

is in the rocks found on Caynham Camp and extensively quarried from the eighteenth

and nineteenth century. The limestone is formed from the dead sea life of that time

and you can find small shells etc. in the stones around the hill today. This era

is known as the Silurian era. It slowly changed to the Devonian era 300 million years

ago when the area, still warmer than today, became dry, the seas receded and the

land looked like the savannah plains in South Africa today. So on top of the dead

coral and mudstone was laid a layer of Devonian rock that became the familiar clay

soils we find in the fields and gardens at the bottom of the hill and throughout

most of the area.

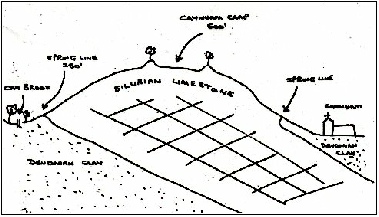

The porous Silurian rock known as an ‘aquifer’ holds the winter rains and releases water slowly into springs and streams. The impervious Devonian clay below the spring line stays wet most of the year and would not be as suitable for settlement in the early human era.

So the first evidence of humans in ‘Caynham’ is the massive earthwork known as Caynham Camp. It was constructed in the late Bronze Age, 900 BC. It continued to be developed and restructured until the Roman invasion of 44 AD. The inhabitants, a race of Celts, grew crops. Grains of wheat were found in the 1960 archaeological dig so they must have cultivated the free draining soil above the spring line. Below the spring line boggy conditions would have prevented cultivation but here they would have hunted for food and other materials.

The numerous post holes in the Camp, with pottery and grain, are evidence that it was a place of habitation and not just a refuge. So far there is a complete lack of evidence of Romans in ‘Caynham’. However we do know the Romans dispersed the Celts’ hill top settlements to prevent rebellion, so what happened to the people of the Camp? The nearest Roman settlements are Cleobury Mortimer and Leintwardine. There was a Roman signalling station at The Sheet. Perhaps somewhere there are some Roman remains waiting to be discovered. Fred Reeves, History teacher at the Grammar School, was always looking for evidence in Ludlow. Is Villa Farm, Greete the site of a Roman Villa? Roman government failed completely by 410 AD, and with it the first Euro Currency!

A less civilised era was heralded by an invasion from the east. Saxons, Angles and Jutes decided Britain is for them and settled or invaded the south in 400’s AD and pushed west over the next 200 years. The Angles of the Hwicce tribe arrive in the area around 550 AD. There must have been heavy fighting with the Romano Celts all the way and most of the evidence points to ethnic cleansing rather than a merging of the two races. All the place names in Caynham are Saxon or later. Cumberley Lane in Knowbury is Saxon for ‘clearing of the Welsh’ the only reference to the Welsh by the Saxons. The early Saxons were farmers who did not live in towns like the Roman Celts. So most of the small Roman Celtic settlements just disappeared without trace so far. The Saxons were however good farmers and had ploughs that could cultivate the wetter soils and the ridge and furrow system kept the soil drier. So to Caega fell the honour of ‘claiming’ the settlement. of Caynham. Maybe on rising ground just below the Camp they fashioned an enclosure as a place to worship their Gods where the church now stands.

Caynham and the Roman Occupation 44 – 410AD

There has been no archaeological evidence of Romans or Romano British in the parish of Caynham so far. Professor Stanford in his book ‘Archaeology of the Welsh Marches’ suggests strongly that British hill forts like Caynham Camp were dispersed so that the real threat of rebellion was minimised. The occupants may also have fled west and joined other fighters there. Stanford also noticed from the air an outline of a small Roman signalling station at The Sheet, only a mile from Caynham and half a mile from the camp itself. A few miles from Caynham are more hill forts : Croft Ambury; Nardy Bank; and Titterstone Clee.

Rebellion against the Roman invasion continued in the area until about AD78, notably Caractacus a British leader from the southeast who finished his fighting in the Shropshire Marches. He and his family were taken to Rome, and made such an impression that the Emperor spared them and they lived their days out in the comfort of Imperial Rome.

There was more fighting around AD160 by which time the Romans had erected a large fort at Leintwardine and a large marching camp at Bromfield. Leintwardine was then known as Bravorium and became the largest Roman settlement in the area being on the ‘motorway’ Watling Street. Romano British settlements grew alongside these well made roads.

No Roman road through Caynham probably means no large Romano-

The capital of the province was Viriconium or present day Wroxeter. That city then

covered 500 acres and was the fourth largest Romano-

Webster speculates that a Roman road existed running North/South through Ludlow which makes sense since at Bromfield there was a large marching camp, and a Roman road runs North from Gloucester/Newent/Bodenham/Kimbolton where the evidence abruptly ends. If there were such a road this would place Caynham within a few miles of it. It would be convenient to surmise that there was continuous occupation in the village from Bronze Age to Silicon Chip Age.

Roman occupation of Britain was failing by AD350 and nearly 300 years of peace was about to descend gradually into disorganisation, tribal disputes, war with the invading Saxons, Angles and Jutes, chaos then a gradual semblance of order again. All this was labelled the Dark Ages by later societies but perhaps it was ‘dark’ because of the small amount of evidence, so far, of organisation and civilisation. In AD410 the Emperor Honorius withdrew all Roman legions from Britannia to defend the Roman frontier nearer home from the Goths. He told the Britons to look to their own for their defence.

Shropshire after the Romans

The Cornovii tribe must have remained relatively organised and centred around Wroxeter, about 26 miles north of Caynham. Archaeological evidence from Wroxeter shows substantial, but less sophisticated building, went on there into the fifth century at the time of leaders like Vortigern and possibly Arthur who successfully fought the Saxon invaders. Arthur’s victory at Mount Baden about AD530 sealed the peace in this area (West Midlands) until at least AD571 when they were defeated by Cathwulf at Bedford in AD571. Another defeat at Dysham in AD577 near Bath and the region was under more threat. Urien of Reged (a northern tribe) provided protection for the Cornovii until his defeat at Catterick in AD598, and by AD614 the Saxon Hethelforth defeated the Celts at Chester with the slaughter of 1000 unarmed monks. Then it was at this time that Caynham became less a part of the Celtic Cornovii tribe, more a district of the Angles from Mercia whose centre of power was around Tamworth in Staffordshire. It is probably safe to assume this had been accomplished by AD650.

By AD660 the Mercian King Paeda became Christian and Caynham, homestead of a man call Caega, must have evolved perhaps in a clearing already previously occupied by the Cornovii, perhaps using the same religious site as the Christian Celts, perhaps that site is now where the present church stands. There are not many places in Shropshire or Herefordshire ending in HAM. Professor Stanford suggests any villages ending in HAM were early Saxon settlements (on ground already cleared by previous occupants – the Celts), and further that HAM signified a place of importance, perhaps someone who might consider himself a powerful ruler of the immediate area. Certainly The Manor of Caynham covered a large area extending into the parishes of Bitterley, Knowbury and Clee Hill and by AD1066 the Saxon village of Caynham was paying £8.00 a year in tax. Out of 56 settlements in South Shropshire, as far north as Church Stretton, this tax was 9th equal highest with Cleobury Mortimer. Only six of the 56 villages had more hides (areas of agricultural land taxable). There were 16 slaves in Caynham, second highest of all 56 villages. Stanton Lacy which included Ludlow in its parish had more slaves.

So by the Norman Conquest Caynham had achieved a higher level of taxation and thus prosperity than 80% of its near neighbours. The Manor of Caynham in late Saxon times was more prosperous than its near neighbours than at any time since. The choice of Ludlow as a post conquest planned town by the Normans must have spelt the end of that position for Caynham because technology moved on, castles, bridges, mills were put in places where previously it was considered too difficult. So Caynham itself was never likely to achieve the position above what it is today – a small rural village.

Sources

Stanford -

Webster -

The Doomsday Book